Pomp Miracles

Graham Wiebe & Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes

Curated by Luther Konadu

Blinkers

Winnipeg, MB

May 14 – July 2, 2022

Press:

︎︎︎ Contemporary Art Library

Graham Wiebe & Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes

Curated by Luther Konadu

Blinkers

Winnipeg, MB

May 14 – July 2, 2022

Press:

︎︎︎ Contemporary Art Library

I’m delighted to be presenting the exhibition Pomp Miracles, an installation of sculptural and photographic works by Winnipeg-based artist Graham Wiebe and Vancouver-based artist Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes featuring a sound contribution from recording and mixing engineer/producer/musician, Nick Short who is also based in Vancouver.

The inception of this collaboration between all of us started over a year ago after years following Wiebe and Holmes’ trajectories in their respective practices. They were united in this project primarily for their shared sensibilities in apprehending photography in their work. This was a general sensibility and approach to the medium that often led to sculptural divergences and even further, material engagements that supplemented, expanded upon, or in several instances, resulted in lateral objects independent of photography. This loose starting point became the bases upon which the exhibit sprung out of. And with that, the artists went off their own paths over the months with an open possibility and they ended near a mid-point of unforeseen convergences that this exhibition contains.

Over the years, Holmes has liberally hopscotched between various photography genres. She has employed her own captured images along with pre-existing stock images, ranging from nature photography, horse racing photography, product photography, concert photography, etc. In this exhibit, we see the latter two (concert and product) deployed. These starting images become a means to an end willfully divergent and irrespective of their point of origin. Through a series of experiments with a home printer, Holmes layers and embellishes product shots of a fake jade deer antique figurine that was for sale on an eBay-like online platform. The jade deer, a historical Chinese artifact of cultural and social significance regarded as an object of good fortune and a symbol of longevity, has been cast in resin resulting in a feeble replica filed under the awkward tag; ‘mid-century Chinoiserie’. Holmes redirects the innate use of the product shots. She veils its surface by feeding the printer with the printed product shots, repeating the process over and over until it is covered with errant printer inkjet marks and scanned drawings which divorces the image further away from its root. In other versions, she doodles, colours, scales up, and fragments the image. To extend this reconstructive engagement with the image, Holmes builds shelves at the base of the final Dibond print creating a kind of provisional relief sculpture stacked with empty drink cans and juice boxes she consumed with Wiebe and I during the installation process. She invites visitors to freely drop off their empties as well, and with their enticing colourful product designs, the cans become an added clutter of flourish to the fake jade image, making it less legible and creating an absurdist detour away from the photograph.

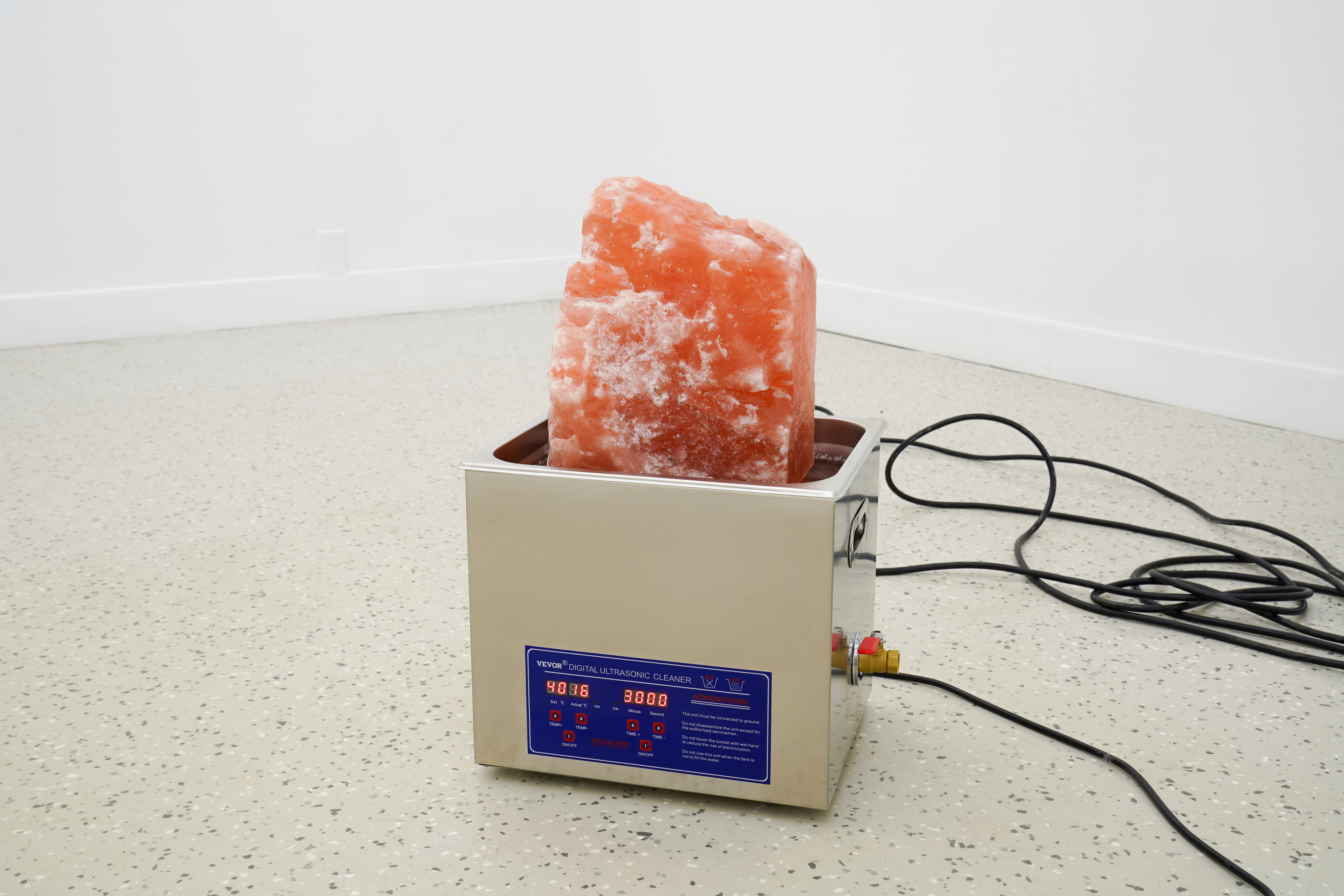

Wiebe, who also holds a healthy ambivalent relationship with photographic images, deploys them more sparingly albeit physically in the exhibition. The aftershocks of a recent tragic event involving a fire that consumed his and several local artists’ studios along with years of work continue to be an animating presence in Wiebe’s recent work. Heat, fire, and electrical circuits are all present traces in the exhibition. A flat-screen electric fireplace is obscured by a perforated cursed image which was once banner ad that followed him through his web browser for weeks. Here, as a perforated print, we see the flames of the electric fireplace looming behind the image, creating a kind of double image. The image/object combinations are extended with their wires cascading haphazardly across the room mimicking a scene from the artist’s former studio where multiple cables and extensions crossed perilously. An impulse that developed from anxieties precipitated by the tragic event saw Wiebe investigating various alternative (read: new age-y) burial, cremation, funeral practices, and the many, at times, skewed ways people cope with grief. It was an impulse I observe as falling between Freud’s description of the death drive and its opposite. Wiebe’s selected objects and sculptural images both make a bid for a kind of ‘transcendence’, maybe divine or maybe not. This elusive middle space is somewhere not in this chaotic world nor in the unknown place of death. Nonetheless, there’s a constant flirtation with that null unknown place. Wiebe is attuned to the growing, often hokey culture of spirituality, healing crystals, inspirational stones, juice-cleanses, all-natural everything, and the unending purchases one can make to reach that transcendent bliss. From this, Wiebe creates his own burial sculptures that include a Himalayan salt rock urn. The Himalayan salt rock urn is a biodegradable water burial option for grievers who want their lost loved ones to be one with nature. The salt rock urn dissolves naturally over time when released into a body of water. Here, Wiebe has devised his own slanted satirical version with an UltraSonic cleaner--a portable dishwasher of --as the container for the fluid that slowly dissolves the salt rock urn over the course of the exhibit. There’s another version of these alternative burial props Wiebe transposes askew in the form of a bonsai tree urn with a biodegradable cooler for a plant pot heated by a hot plate. It is also another burial trend where deceased loved ones’ ashes are used as fertilizers or soil for germinating new life. The urns are used as the plant pot that feeds this new growth. The bonsai tree, long before it was brought to North America, has a history tracing back to Japanese Zen Buddhism where it gained its name and before that, adopted from an even longer Chinese horticultural craft history, often practiced by the wealthy. It is part of these histories that the bonsai tree we know today continues to be viewed in some contexts as a symbol of good fortune, peace, harmony, and rife with meditative qualities. Wiebe’s bonsai tree, like Holmes jade, are both fake although both are symbols associated with good luck. They are removed from the actual. They make empty promises. These objects and images of objects urge to get closer to something beyond but come up with mere chimera. Photos have a way of seducing with believable illusions and both Wiebe and Holmes are aware and okay with its transitory alluring surface. For them, it is a starting point to dwell even if temporarily.

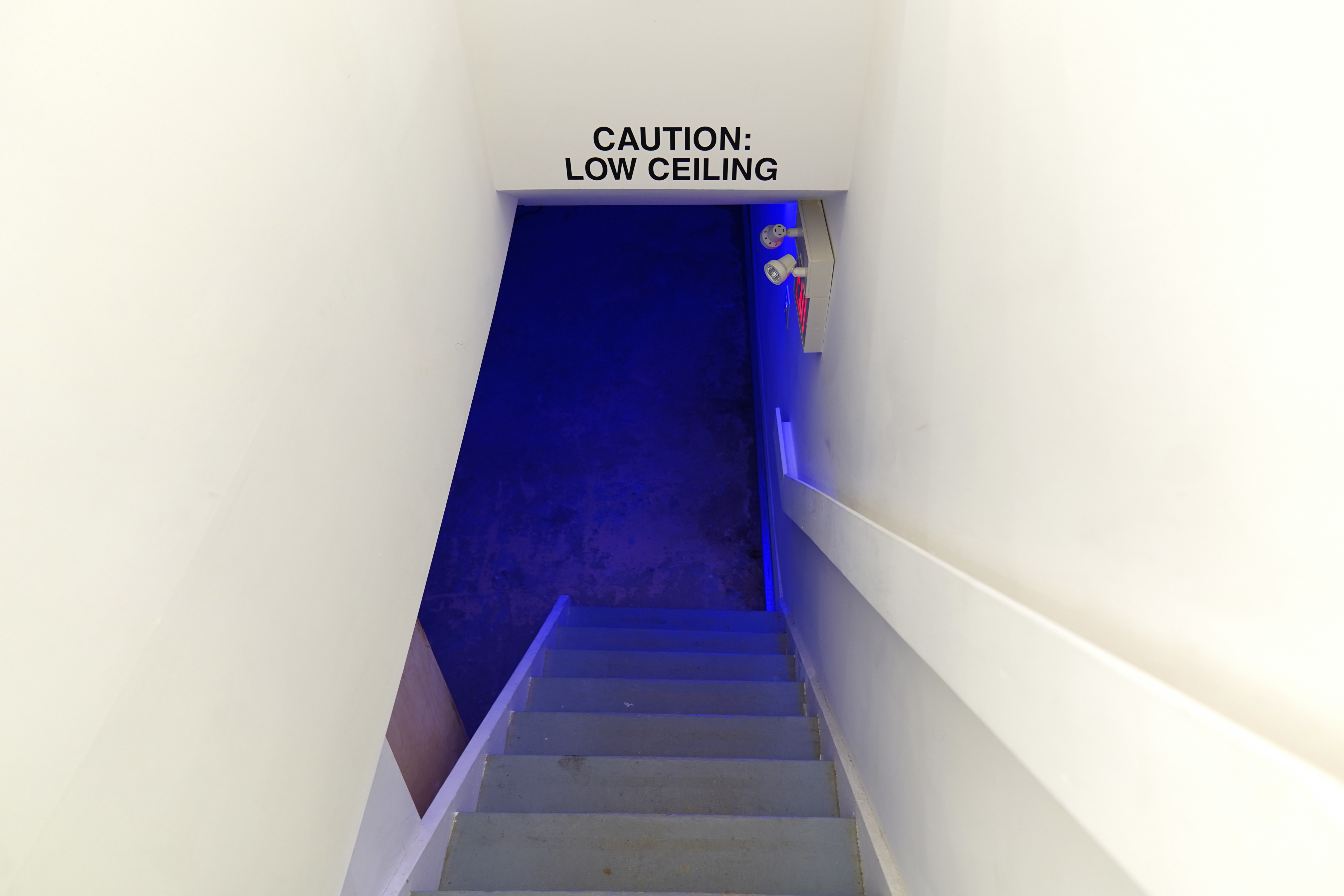

In the basement level of the exhibition, bathed in luminous blue light, Holmes has installed a concert photograph in the form of a wheat-pasted poster. The picture taken by Holmes in 2010 is of an Uffie concert in Hong Kong from 2010. It's a scene of revelry stuck in time. Holmes uses her characteristic decorative distortion to re-engage the photo and the umbilical cord to that past, to being there, in that pomp, that elation, if briefly. Playing ambiently is a slow-moving drone-y soundtrack by Nick Short, Holmes’ partner, and collaborator. It's an audio response to another more private concert documentation of sorts in the form of a video Holmes captured of her friends’ hands as they hover and hesitate to play notes on the piano and drums--as if edging the cathartic release music can produce.

‘Pomp Miracles’ is the result of a word collage generated between the artists and I. It made sense once we arrived at it. It serves as an overarching term for what the objects, images, and gestures in the exhibit do or what they suggest to be doing. Pomp, because it speaks to the surface energy the works engage in-- whether purposefully goofy or resplendent excess. It is rather apropos that the word ‘pomp’ looks and sounds like the word ‘pump’ which can mean to inflate or give the appearance of solidity to an object (tire or balloon) with just air, a description not so far removed from ‘pomp’ which is about the appearance of things. In some colloquial languages pump means to embolden as in, ‘to get pumped up’ or to be ‘hyped’ or ‘juiced up’ (caffeine, sugar, etc) on a temporary high in order to get by. A muscle pump is a kind of transient energy and artifice that makes one’s muscles appear fuller than they actually are. A common behind-the-scenes photoshoot practice is to have dumbbells on set. This is more prevalent where male models are the subjects. Before getting in front of the camera to appear jacked, models are known to do a few preparatory bicep curl reps with the dumbbells or perhaps push-ups. But of course, it all deflates in a manner of hours after the ceremony (or pomp) of photographing ends.

The other half of our word-collage, Miracles, was considered as a shorthand for something other, an enduring salve maybe, a yearning for something that can’t be readily accessed, in full at least, and as such, the splendour of its foreshortened facsimile becomes a passable resolve.

- Luther Konadu

The inception of this collaboration between all of us started over a year ago after years following Wiebe and Holmes’ trajectories in their respective practices. They were united in this project primarily for their shared sensibilities in apprehending photography in their work. This was a general sensibility and approach to the medium that often led to sculptural divergences and even further, material engagements that supplemented, expanded upon, or in several instances, resulted in lateral objects independent of photography. This loose starting point became the bases upon which the exhibit sprung out of. And with that, the artists went off their own paths over the months with an open possibility and they ended near a mid-point of unforeseen convergences that this exhibition contains.

Over the years, Holmes has liberally hopscotched between various photography genres. She has employed her own captured images along with pre-existing stock images, ranging from nature photography, horse racing photography, product photography, concert photography, etc. In this exhibit, we see the latter two (concert and product) deployed. These starting images become a means to an end willfully divergent and irrespective of their point of origin. Through a series of experiments with a home printer, Holmes layers and embellishes product shots of a fake jade deer antique figurine that was for sale on an eBay-like online platform. The jade deer, a historical Chinese artifact of cultural and social significance regarded as an object of good fortune and a symbol of longevity, has been cast in resin resulting in a feeble replica filed under the awkward tag; ‘mid-century Chinoiserie’. Holmes redirects the innate use of the product shots. She veils its surface by feeding the printer with the printed product shots, repeating the process over and over until it is covered with errant printer inkjet marks and scanned drawings which divorces the image further away from its root. In other versions, she doodles, colours, scales up, and fragments the image. To extend this reconstructive engagement with the image, Holmes builds shelves at the base of the final Dibond print creating a kind of provisional relief sculpture stacked with empty drink cans and juice boxes she consumed with Wiebe and I during the installation process. She invites visitors to freely drop off their empties as well, and with their enticing colourful product designs, the cans become an added clutter of flourish to the fake jade image, making it less legible and creating an absurdist detour away from the photograph.

Wiebe, who also holds a healthy ambivalent relationship with photographic images, deploys them more sparingly albeit physically in the exhibition. The aftershocks of a recent tragic event involving a fire that consumed his and several local artists’ studios along with years of work continue to be an animating presence in Wiebe’s recent work. Heat, fire, and electrical circuits are all present traces in the exhibition. A flat-screen electric fireplace is obscured by a perforated cursed image which was once banner ad that followed him through his web browser for weeks. Here, as a perforated print, we see the flames of the electric fireplace looming behind the image, creating a kind of double image. The image/object combinations are extended with their wires cascading haphazardly across the room mimicking a scene from the artist’s former studio where multiple cables and extensions crossed perilously. An impulse that developed from anxieties precipitated by the tragic event saw Wiebe investigating various alternative (read: new age-y) burial, cremation, funeral practices, and the many, at times, skewed ways people cope with grief. It was an impulse I observe as falling between Freud’s description of the death drive and its opposite. Wiebe’s selected objects and sculptural images both make a bid for a kind of ‘transcendence’, maybe divine or maybe not. This elusive middle space is somewhere not in this chaotic world nor in the unknown place of death. Nonetheless, there’s a constant flirtation with that null unknown place. Wiebe is attuned to the growing, often hokey culture of spirituality, healing crystals, inspirational stones, juice-cleanses, all-natural everything, and the unending purchases one can make to reach that transcendent bliss. From this, Wiebe creates his own burial sculptures that include a Himalayan salt rock urn. The Himalayan salt rock urn is a biodegradable water burial option for grievers who want their lost loved ones to be one with nature. The salt rock urn dissolves naturally over time when released into a body of water. Here, Wiebe has devised his own slanted satirical version with an UltraSonic cleaner--a portable dishwasher of --as the container for the fluid that slowly dissolves the salt rock urn over the course of the exhibit. There’s another version of these alternative burial props Wiebe transposes askew in the form of a bonsai tree urn with a biodegradable cooler for a plant pot heated by a hot plate. It is also another burial trend where deceased loved ones’ ashes are used as fertilizers or soil for germinating new life. The urns are used as the plant pot that feeds this new growth. The bonsai tree, long before it was brought to North America, has a history tracing back to Japanese Zen Buddhism where it gained its name and before that, adopted from an even longer Chinese horticultural craft history, often practiced by the wealthy. It is part of these histories that the bonsai tree we know today continues to be viewed in some contexts as a symbol of good fortune, peace, harmony, and rife with meditative qualities. Wiebe’s bonsai tree, like Holmes jade, are both fake although both are symbols associated with good luck. They are removed from the actual. They make empty promises. These objects and images of objects urge to get closer to something beyond but come up with mere chimera. Photos have a way of seducing with believable illusions and both Wiebe and Holmes are aware and okay with its transitory alluring surface. For them, it is a starting point to dwell even if temporarily.

In the basement level of the exhibition, bathed in luminous blue light, Holmes has installed a concert photograph in the form of a wheat-pasted poster. The picture taken by Holmes in 2010 is of an Uffie concert in Hong Kong from 2010. It's a scene of revelry stuck in time. Holmes uses her characteristic decorative distortion to re-engage the photo and the umbilical cord to that past, to being there, in that pomp, that elation, if briefly. Playing ambiently is a slow-moving drone-y soundtrack by Nick Short, Holmes’ partner, and collaborator. It's an audio response to another more private concert documentation of sorts in the form of a video Holmes captured of her friends’ hands as they hover and hesitate to play notes on the piano and drums--as if edging the cathartic release music can produce.

‘Pomp Miracles’ is the result of a word collage generated between the artists and I. It made sense once we arrived at it. It serves as an overarching term for what the objects, images, and gestures in the exhibit do or what they suggest to be doing. Pomp, because it speaks to the surface energy the works engage in-- whether purposefully goofy or resplendent excess. It is rather apropos that the word ‘pomp’ looks and sounds like the word ‘pump’ which can mean to inflate or give the appearance of solidity to an object (tire or balloon) with just air, a description not so far removed from ‘pomp’ which is about the appearance of things. In some colloquial languages pump means to embolden as in, ‘to get pumped up’ or to be ‘hyped’ or ‘juiced up’ (caffeine, sugar, etc) on a temporary high in order to get by. A muscle pump is a kind of transient energy and artifice that makes one’s muscles appear fuller than they actually are. A common behind-the-scenes photoshoot practice is to have dumbbells on set. This is more prevalent where male models are the subjects. Before getting in front of the camera to appear jacked, models are known to do a few preparatory bicep curl reps with the dumbbells or perhaps push-ups. But of course, it all deflates in a manner of hours after the ceremony (or pomp) of photographing ends.

The other half of our word-collage, Miracles, was considered as a shorthand for something other, an enduring salve maybe, a yearning for something that can’t be readily accessed, in full at least, and as such, the splendour of its foreshortened facsimile becomes a passable resolve.

- Luther Konadu

Final Pictures

2022

vacuum sealed coffee carafe, water, sodium carbonate, ascorbic acid, potassium bromide, instant coffee, kodak 400 tmax film, rubber drain stopper, steel

5.5 x 5 x 10 in

2022

vacuum sealed coffee carafe, water, sodium carbonate, ascorbic acid, potassium bromide, instant coffee, kodak 400 tmax film, rubber drain stopper, steel

5.5 x 5 x 10 in

Keys

2022

firepokers, steel

dimensions variable

2022

firepokers, steel

dimensions variable

Keys

2022

(detail)

2022

(detail)

Study for a Water Burial

2022

ultrasonic cleaner, water, salt rock, extension cord

20 x 12.5 x 10.5 in

2022

ultrasonic cleaner, water, salt rock, extension cord

20 x 12.5 x 10.5 in

87 year old personal trainer shares her secrets to losing weight in 2014

2022

electric fireplace, perforated vinyl, extension cord

71.5 x 21.5 x 5.5 in

2022

electric fireplace, perforated vinyl, extension cord

71.5 x 21.5 x 5.5 in

87 year old personal trainer shares her secrets to losing weight in 2014

2022

(detail)

2022

(detail)

Little-known bitcoin loophole exposed and doctors are not happy

2022

electric fireplace, perforated vinyl, extension cord

21.5 x 101 x 5.5 in

2022

electric fireplace, perforated vinyl, extension cord

21.5 x 101 x 5.5 in

Little-known bitcoin loophole exposed and doctors are not happy

2022

(detail)

2022

(detail)

Study for a Greener Burial

2022

hot plate, compostable cooler, plastic bonsai tree, extension cord

25 x 20 x 14 in

2022

hot plate, compostable cooler, plastic bonsai tree, extension cord

25 x 20 x 14 in