Inspirational Stones

MFA Thesis Exhibition

Audain Gallery, University of Victoria

Victoria, BC

March 8 – 12, 2021

Press:

Public Parking

MFA Thesis Exhibition

Audain Gallery, University of Victoria

Victoria, BC

March 8 – 12, 2021

Press:

Public Parking

Do you ever imagine the photograph that will accompany your obituary or funeral? What likeness do you want to be memorialised by, gazing out in your place at your loved ones and mourners? Will you be smiling, exuding warmth? Or serious, looking back on your life, accomplishments, and memories in earnest? What will you wear?

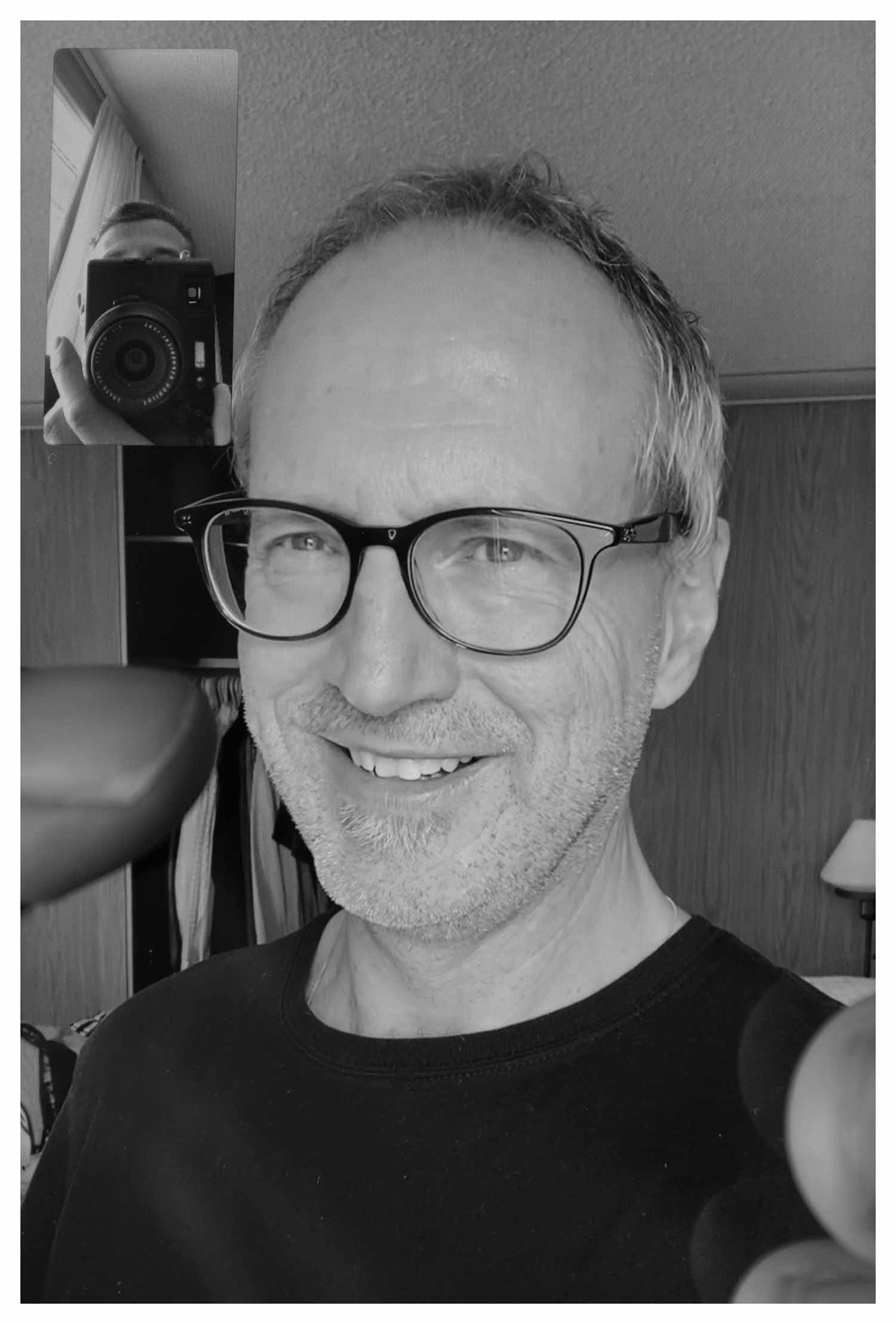

Artist Graham Wiebe’s parents asked him to take their obituary photographs this year. Initially, he was reluctant. They are still young, their potential deaths seemed too far off to plan the necessary imagery just yet. But, he obliged. They wanted to be happy with the images, with their likeness, when the time comes that they’re needed. Taken over FaceTime, the photographs (Early Obituary (Mom) and Early Obituary (Dad), both 2021) show Graham, obscured by his camera in the upper left of the frame. His mother’s face is warm, gazing out past the lens with a gently open smile. His dad is slightly cheekier, with dark rimmed glasses and a stubbly beard. In both black and white images, stuff of an un-staged home is visible behind: a mirror, a stack of books, an open closet with clothes in it. These are intimate portraits, shot from afar. In each, slightly blurred, zoomed-in fingertips, presumably Graham’s, push their way into the edge of the frame. Leaning against the wall, held up by two supports each of two hands held to make a heart shape, 3D printed in white plastic, these two large photographic prints face you as you enter the exhibition, and foreshadow its themes: loss and care.

Graham’s practice, prior to his MFA studies, was almost entirely photographic; black and white, snapshot aesthetic, a fan of Wolfgang Tillmans, exploring ideas of truth and deceit. But the obituary photographs are the only lens-based works in Inspirational Stones, his MFA thesis show at the Audain Gallery of the University of Victoria. A month before he moved from Winnipeg to Victoria in Autumn of 2019, the three-story warehouse which spanned a city block in which Graham kept his studio in Winnipeg’s North End burned to the ground. The fire smoldered for a week. Graham, like the 26 other artists who had studios in the warehouse, lost his space to work, his archive, his collection of books, his works in progress, most of his equipment, and the physical community connected by the complex. He also felt an (unsubstantiated, but understandable) worry that maybe it was his fault, maybe he left too many plugs in a power bar, maybe one overheated. Grad school, in its most common incarnation, is supposed to force you to break your practice back down in order to interrogate it and build it up again. The fire did that for Graham, who arrived in Victoria with a blank slate, a literal pile of ash.

It’s easy to be melancholy with the aesthetic here: heavily black, a goth look with doses of self-help for lightness. The resulting impression of the installation isn’t somber though, it’s hopeful. I remember commenting to Graham on the resonance with John Baldessari’s Cremation Project (1970)on a studio visit in late 2019, before much of this work was made, and before the pandemic consumed daily life. ‘But of course,’ I added, realising my crass-ness, ‘Baldessari chose to burn his works! You didn’t!’ You can’t plan a catastrophe.

Like many West Coast cities, Victoria has a presence of new age and self-care culture; yoga studios, gyms, and stores promoting objects and practices for healing and self-preservation are everywhere here. This small city in which Graham now lives is also rife with thrift stores, possibly due in part to its significant elderly population who retire here for its temperate climate. The contents of estate sales often recirculates through these shops. Many of the objects worked into the sculptures and installations of Inspirational Stones were found in these stores. Others are things Graham found on curbs, left abandoned by their owners or with ‘free’ signs on them. A white bike helmet with a face shield that speaks the brand name: “No Fear.” Hollow black speaker boxes. A white ‘Love’ interior sign written in a cursive script. Yogi sculptures. An essential oil diffuser. Activated charcoal. Graham was on a bus, heading out to a cemetery near one of the many beaches, early in his time in this city, when another passenger caught his eye. She kept removing a pebble from her pocket, engraved with the word “peace.” He observed the passenger rolling it over in her hand, gazing at the word as if trying to manifest “peace” through her act of looking. Objects of the corporatising of serenity culture and of self-care, these objects spin as capital in an endless cycle. Repurposed and repositioned in the installation, Graham makes the objects become strange. In You Are Beautiful (2021) a found cash register drawer is filled with activated charcoal, upon which the aforementioned crying yogi sculpture sits, a pinky stone-looking plastic, cracked up one side and held together with crude staples. In place of cash, the drawer is stuffed with a white quilted pillow. The eponymous affirmation comes from a sticker placed on the front of the till, maybe to remind whichever minimum-wage paid service worker used it, that they, in fact, are. In No Fear (2021) the white helmet sits atop a cream toilet paper roll holder from the 70s or 80s, embossed with a flower pattern, itself atop a stack of weights and a white lace doily. From the front guard of the helmet, which points skywards, the assemblage vomits a spout of black, dead, local weeds. Objects for self-care and self-preservation, for beautifying items of utility like toilet paper, are immortalised for their futility.

The strangest work in the show is an installation that could easily be missed. Look up, and in the fluorescent lights Graham has sprinkled black, plastic flies. With the plastic sheeting of the light replaced, all that remains is a shadow of specks of something that might be dead flies suspended over the installation. Mark Fisher wrote about “that which does not belong,” in his 2016 book, The Weird and the Eerie. Fisher explored things or experiences that don’t fit our perception because they are artificial, rather than natural, things that defy linguistic explanation because they are slightly beyond our conception.1

In Rumaan Alam’s 2020 novel Leave the World Behind, the protagonist Amy, a middle-aged Manhattonite on a family vacation in the Hamptons, flippantly daydreams of her husband’s death. “I would love again,” she resolves, then swiftly checking her email on her iPhone before an unseen apocalypse hits. Apocalypse or not, most of us are going to get sick eventually, we’re all going to die. We all have that in common. What comes after loss? Inspirational Stones asks us. Inevitably, change.

- Kim Dhillon

1. See Elvia Wilk, “Toward a Theory of the New Weird,” Literary Hub, 5 August, 2019 https://lithub.com/toward-a-theory-of-the-new-weird/?single=true

Artist Graham Wiebe’s parents asked him to take their obituary photographs this year. Initially, he was reluctant. They are still young, their potential deaths seemed too far off to plan the necessary imagery just yet. But, he obliged. They wanted to be happy with the images, with their likeness, when the time comes that they’re needed. Taken over FaceTime, the photographs (Early Obituary (Mom) and Early Obituary (Dad), both 2021) show Graham, obscured by his camera in the upper left of the frame. His mother’s face is warm, gazing out past the lens with a gently open smile. His dad is slightly cheekier, with dark rimmed glasses and a stubbly beard. In both black and white images, stuff of an un-staged home is visible behind: a mirror, a stack of books, an open closet with clothes in it. These are intimate portraits, shot from afar. In each, slightly blurred, zoomed-in fingertips, presumably Graham’s, push their way into the edge of the frame. Leaning against the wall, held up by two supports each of two hands held to make a heart shape, 3D printed in white plastic, these two large photographic prints face you as you enter the exhibition, and foreshadow its themes: loss and care.

Graham’s practice, prior to his MFA studies, was almost entirely photographic; black and white, snapshot aesthetic, a fan of Wolfgang Tillmans, exploring ideas of truth and deceit. But the obituary photographs are the only lens-based works in Inspirational Stones, his MFA thesis show at the Audain Gallery of the University of Victoria. A month before he moved from Winnipeg to Victoria in Autumn of 2019, the three-story warehouse which spanned a city block in which Graham kept his studio in Winnipeg’s North End burned to the ground. The fire smoldered for a week. Graham, like the 26 other artists who had studios in the warehouse, lost his space to work, his archive, his collection of books, his works in progress, most of his equipment, and the physical community connected by the complex. He also felt an (unsubstantiated, but understandable) worry that maybe it was his fault, maybe he left too many plugs in a power bar, maybe one overheated. Grad school, in its most common incarnation, is supposed to force you to break your practice back down in order to interrogate it and build it up again. The fire did that for Graham, who arrived in Victoria with a blank slate, a literal pile of ash.

It’s easy to be melancholy with the aesthetic here: heavily black, a goth look with doses of self-help for lightness. The resulting impression of the installation isn’t somber though, it’s hopeful. I remember commenting to Graham on the resonance with John Baldessari’s Cremation Project (1970)on a studio visit in late 2019, before much of this work was made, and before the pandemic consumed daily life. ‘But of course,’ I added, realising my crass-ness, ‘Baldessari chose to burn his works! You didn’t!’ You can’t plan a catastrophe.

Like many West Coast cities, Victoria has a presence of new age and self-care culture; yoga studios, gyms, and stores promoting objects and practices for healing and self-preservation are everywhere here. This small city in which Graham now lives is also rife with thrift stores, possibly due in part to its significant elderly population who retire here for its temperate climate. The contents of estate sales often recirculates through these shops. Many of the objects worked into the sculptures and installations of Inspirational Stones were found in these stores. Others are things Graham found on curbs, left abandoned by their owners or with ‘free’ signs on them. A white bike helmet with a face shield that speaks the brand name: “No Fear.” Hollow black speaker boxes. A white ‘Love’ interior sign written in a cursive script. Yogi sculptures. An essential oil diffuser. Activated charcoal. Graham was on a bus, heading out to a cemetery near one of the many beaches, early in his time in this city, when another passenger caught his eye. She kept removing a pebble from her pocket, engraved with the word “peace.” He observed the passenger rolling it over in her hand, gazing at the word as if trying to manifest “peace” through her act of looking. Objects of the corporatising of serenity culture and of self-care, these objects spin as capital in an endless cycle. Repurposed and repositioned in the installation, Graham makes the objects become strange. In You Are Beautiful (2021) a found cash register drawer is filled with activated charcoal, upon which the aforementioned crying yogi sculpture sits, a pinky stone-looking plastic, cracked up one side and held together with crude staples. In place of cash, the drawer is stuffed with a white quilted pillow. The eponymous affirmation comes from a sticker placed on the front of the till, maybe to remind whichever minimum-wage paid service worker used it, that they, in fact, are. In No Fear (2021) the white helmet sits atop a cream toilet paper roll holder from the 70s or 80s, embossed with a flower pattern, itself atop a stack of weights and a white lace doily. From the front guard of the helmet, which points skywards, the assemblage vomits a spout of black, dead, local weeds. Objects for self-care and self-preservation, for beautifying items of utility like toilet paper, are immortalised for their futility.

The strangest work in the show is an installation that could easily be missed. Look up, and in the fluorescent lights Graham has sprinkled black, plastic flies. With the plastic sheeting of the light replaced, all that remains is a shadow of specks of something that might be dead flies suspended over the installation. Mark Fisher wrote about “that which does not belong,” in his 2016 book, The Weird and the Eerie. Fisher explored things or experiences that don’t fit our perception because they are artificial, rather than natural, things that defy linguistic explanation because they are slightly beyond our conception.1

In Rumaan Alam’s 2020 novel Leave the World Behind, the protagonist Amy, a middle-aged Manhattonite on a family vacation in the Hamptons, flippantly daydreams of her husband’s death. “I would love again,” she resolves, then swiftly checking her email on her iPhone before an unseen apocalypse hits. Apocalypse or not, most of us are going to get sick eventually, we’re all going to die. We all have that in common. What comes after loss? Inspirational Stones asks us. Inevitably, change.

- Kim Dhillon

1. See Elvia Wilk, “Toward a Theory of the New Weird,” Literary Hub, 5 August, 2019 https://lithub.com/toward-a-theory-of-the-new-weird/?single=true

Early Obituary (Mom)

2021

archival inkjet print, 3d printed heart hand supports, artist frame

62 x 42 in

2021

archival inkjet print, 3d printed heart hand supports, artist frame

62 x 42 in

Early Obituary (Dad)

2021

archival inkjet print, 3d printed heart hand supports, artist frame

62 x 42 in

2021

archival inkjet print, 3d printed heart hand supports, artist frame

62 x 42 in

NO FEAR

2020

weights, doily, toilet paper holder, motocross helmet, dried weeds

57 x 33 x 33 in

2020

weights, doily, toilet paper holder, motocross helmet, dried weeds

57 x 33 x 33 in

you are beautiful

2021

cash register, decal, pillow, charcoal, fire extinguisher, crying yogi statue

16 x 20 x 26 in

2021

cash register, decal, pillow, charcoal, fire extinguisher, crying yogi statue

16 x 20 x 26 in

Love

2021

fake campfire, blinds, speaker cabinets, essential oil diffuser, floor vent, wooden sign, extension cord, iron fence

55 x 27 x 12 in

2021

fake campfire, blinds, speaker cabinets, essential oil diffuser, floor vent, wooden sign, extension cord, iron fence

55 x 27 x 12 in

Night Lights (SAD Lamp)

2020

extension cord, power bar, night lights

5 x 48 x 4 in

2020

extension cord, power bar, night lights

5 x 48 x 4 in

KILL YOUR EGO

2021

pleather padded workout bench, curtain rod hangers, jersey, plastic roses

44 x 11 x 9 in

2021

pleather padded workout bench, curtain rod hangers, jersey, plastic roses

44 x 11 x 9 in

Flies

2021

plastic flies

dimensions variable

2021

plastic flies

dimensions variable